Notes on Death Stranding

I’m playing the first Death Stranding right now, which is also the first Kojima game I’ve taken very far. I think it works marvelously, and does so while charting a course that is very much its own. Here are a few notes from my playthrough.

1. What is it about? I won’t have too much to say about the game’s story, largely because I’m not finished. Most video game writing is basically self-serious B-movie writing (and most supposed examples of actually good video game writing are really no better), and this isn’t that, more because it sets out in its own surreal direction than because it succeeds at being a strong traditional script. The basic premise is that some scientific advancements led to the discovery of the partly-mental, partly-physical realms of the dead, and that the use of new technologies caused the souls of the dying becoming trapped in our world (stranded dead, the ‘Death Stranding,’ you get it). This resulted in massive explosions called “voidouts,” and the destruction of most of the world’s cities and population. As you march across the former United States—rapidly geologically transformed because of “timefall,” a sort of acid rain that rapidly ages anything it touches—you deliver packages and connect cities and preppers hidden in bunkers to a communications network and a re-emerging American government. This, by the way, is my summary as someone currently playing the game, not as someone looking up what the hell is happening on a Wiki, so assume I got part of that wrong.

Death Stranding asks the player fairly directly to consider the potential both for isolation and for connection created by the internet, the effects of a societal addiction to online shopping and delivery services, the risk of environmental disaster and the terrible need for further consumption of material resources in order to withstand its effects, our attachments to the dead, and lots more. All of this is interesting to me. But is it actually a good yarn? I’m not sure yet, but it’s holding my attention. The baby attached to your player character, who helps you detect ghosts, is very cute and drives much of the immediate narrative.

2. Friction. Death Stranding is full of it; you could argue it is made of it. In the context of video games, ‘friction’ typically refers to some amount of resistance that must be withstood or overcome to accomplish something. This has become a popular subject in games criticism; for a while the trend was to make gameplay as frictionless as possible, which it turns out translates to making games as lifeless as possible (the logical conclusion of that design trend is the degenerate ‘idle game,’ which runs on your phone while you do something else and occasionally check in to press a few buttons and continue your progress.)

The concept of friction has become more discussed in the last decade, so it seems to me, mostly because a handful of games were well-received despite not doing everything to make the experience as smooth as possible for the player. (Death Stranding included; certainly also Red Dead Redemption II, Hidetaka Miyazaki’s Dark Souls series, the recent Zelda games, especially if you turn off certain UI features). These games embraced the idea that the player but can actually find the experience more rewarding when basic actions like traversing the map or repairing equipment involve some difficulty and tediousness. These design choices are usually controversial, as plenty of critics feel that such mechanics do not “respect their time.” I feel the opposite; it is the frictionless game which, in demanding nothing of me, demands that I waste 60 hours of my time on purely passive entertainment.

Death Stranding is made of friction, then, because traversing the map, with great difficulty, while carrying a pile of boxes on your back and avoiding ghosts is the core gameplay loop, not the way you get from one ‘fun part’ to another. As a post-apocalyptic “porter,” your job is to carry packages from bunker city to bunker city while rebuilding a communication network along the way. This gets easier as you build more infrastructure for yourself—ladders, climbing anchors, eventually roads—but your interaction with the ground under your feet as you crisscross the map is the primary game action. Remembering to check the weather forecast, not panicking when you have to walk quietly through a sea of the restless dead, and finding a viable path through difficult terrain are the primary sorts of inputs the player has. These are the sorts of interactions which force you to observe minute details, learning which routes work best on foot, which work well on your bike, which can’t be crossed with a truck. Rather than blasting through the landscape to get to a checkpoint, the player works intimately with the opportunities and obstacles presented by the world, becoming more skilled at reading it over time, shrinking its vastness only through careful attention and a dedication to (obsession with) well-placed infrastructure.

3. ‘Cinematic’ games? This transport-focused gameplay necessarily places more emphasis on what sort of atmosphere the game manages to cultivate, because it needs to provide a world and an aesthetic that you don’t mind ‘doing’ very little in even as you have to stay mentally engaged. Setting this mood well, making exploration and traversal feel intrinsically meaningful, is something that these well-received, more demanding games I mentioned above share. Death Stranding is tense, beautiful, and contemplative. It creates a world you care about trying to repair.

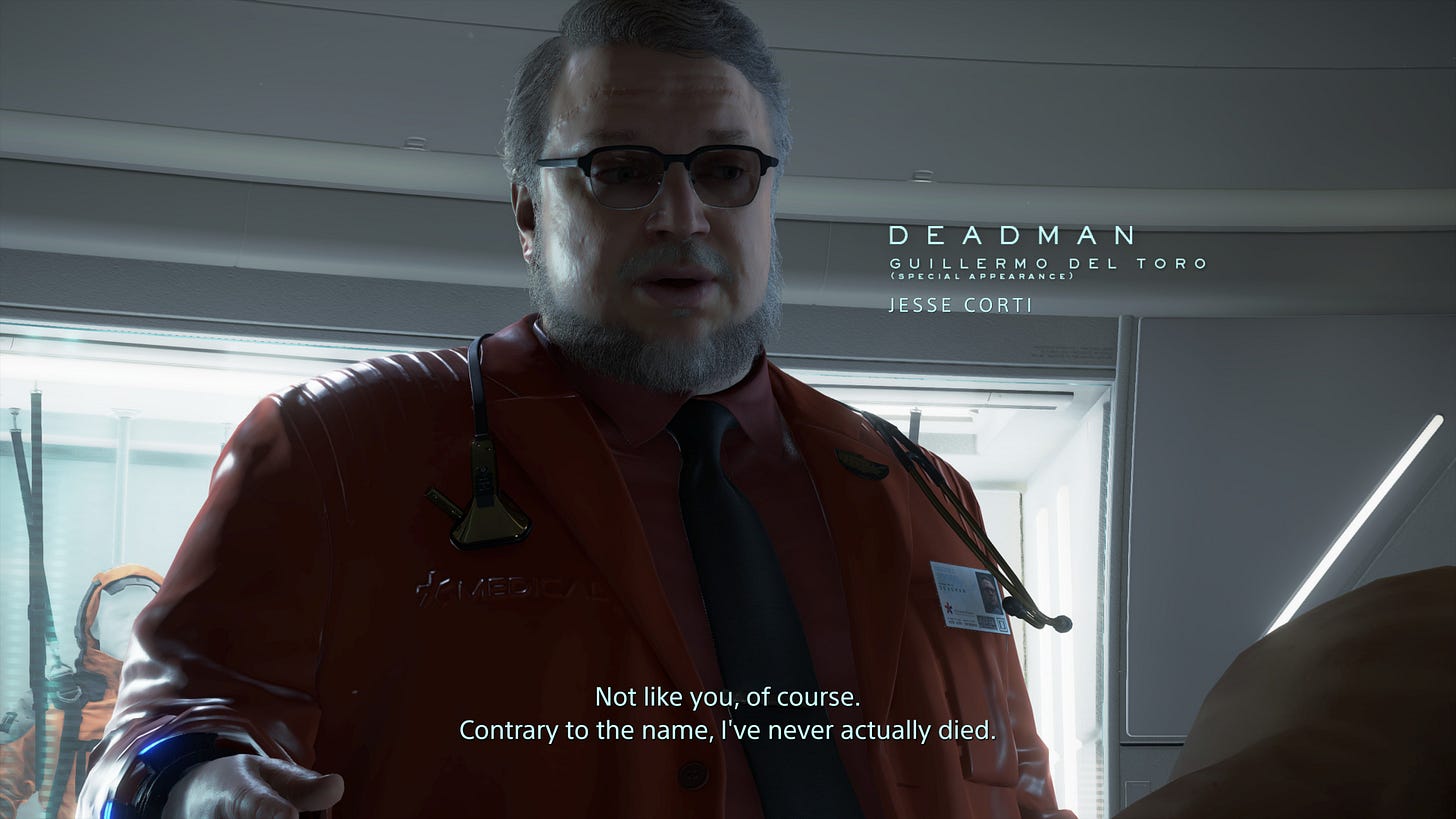

To that end, there is nothing inherently surprising about a game attempting to be “cinematic,” but I think that’s actually a poor encapsulation of what Death Stranding’s stylistic elements accomplish. It has, of course, a strong cast of Hollywood actors (Léa Seydoux, Mads Mikkelsen, Margaret Qualley, Norman Reedus) who perform extensive motion-captured cutscenes. The actors themselves are heavily foregrounded; whenever a major character is first introduced, their name appears onscreen alongside that of the actor playing them. Much the same for the wonderful camera-pans that occur in the midst of certain treks, zooming out and playing a licensed track; the name of the song and artist appear, breaking the fourth wall but not the immersion, signaling that you should understand your own trekking as part of a multimedia set-piece.

I don’t think the effect of this is to make Death Stranding feel anything like a movie, the way Red Dead often does; it creates, rather, a sense of individual curation on the part of the game’s director that is in line with the marketing as an ‘auteur’-ish Hideo Kojima production. You are playing the work of a taste-maker whose studio bears his name, whose fans get excited when he mention in interviews why he fell in love with a particular actor or song and had to include it in his game, whose projects are announced with trailers years before they come out, of which the main point is that the game is his and that his creative control is total. That is completely fine, and in fact it works exceedingly well in the game itself, because Kojima has good—if occasionally corny, occasionally oddball-for-oddball’s-sake—taste. The emphasis on the actors and the licensed music is less about the ‘cinematic,’ then. It is instead a way of emphasizing that this big-budget game is starkly different from anything else you’ve played, because it is curated by a person who is not interested in making normal games. Perhaps that’s a bit pretentious, but it’s also undeniably true; and more generally, big-budget games will become artistically compelling the more audiences are excited about individual, distinctive visions like Kojima’s or Miyazaki’s rather than grey, amorphous military shooters from major publisher-owned studios. So I don’t mind the ‘branding.’

4. “Death Stranding" - what does that mean? One meaning is the event I mentioned above, in which the dead become trapped in the world of the living, resulting in a kind of environmental disaster. But like much else in this world (“Bridge,” “connected,” etc.), these terms are repurposed for and referenced by other elements in the game, creating an eerie sense that persons and entities have spiritual connections which shape their names and fates. (Not to mention some of the character names—’Deadman,’ ‘Die-Hardman,’ ‘Heartman.’) So, ‘Death Stranding’ refers to the inciting incident in the game’s world, but it also refers to the beaches (i.e. strands) which are each individual’s afterlife, and to the fact that the substance which you use to connect the world back up has unique properties which connect it to the world of the dead. So you are using this death-matter to tie the world back together into a ‘knot,’ and the game’s cities all have “Knot’ in their name. You are death-stranding the world. (Your first and most basic weapon, a non-lethal rope that you tie people up with because killing them would cause an explosion, is also called a “strand.”) The names in this world have an overdetermination which gives Death Stranding both a distinct stylistic sensibility, and give it a bit of an occult-y feeling that is in keeping with the anthroposophy-adjacent scientific theories of the game’s fictional world.